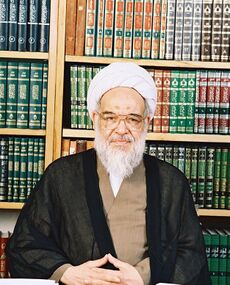

Abbasali Amid Zanjani

| |

| Name | Abbasali Amid Zanjani |

|---|---|

| Age | 1316 SH - 1390 SH |

| Position | Mujtahid, jurist, and university professor |

| Denomination | Shia |

| Nationality | Iranian |

| Speciality | Political jurisprudence and law |

| Works in contemporary jurisprudence | Ten-volume collection of political jurisprudence and several other works |

| Professors | Seyyed Mohammad Hossein Boroujerdi, Sayyid Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini |

- Abstract

Abbasali Amid Zanjani (1316-1390 SH) was an Iranian Shia *mujtahid* and an expert in the fields of political jurisprudence and law. Amid Zanjani was a graduate of both the Qom Seminary and the Najaf and experienced representation in the parliament, teaching at universities, and the presidency of Tehran University in the Islamic Republic. He taught constitutional law and general Islamic law in academic and scientific centers and had numerous writings in these two arenas, of which the ten-volume collection of political jurisprudence is the most famous.

Amid Zanjani believes in absolute wilayat al-faqih in political jurisprudence and the structure of Islamic government but considers it compatible with the people's right to vote. He believes in political development and the expansion of freedoms. He considers justice to be the most fundamental concept of political jurisprudence, and on this basis, he proposes public oversight of the Islamic government. In the field of human rights, he believes in dignity and equality of human beings and has written that religious minorities in Islamic government, even if they pay *jizya*, enjoy many rights according to the *dhimma* contract and, contrary to popular belief, are not humiliated. In his view, apostasy is, in fact, a renunciation of political citizenship, and its ruling is determined by the court.

Scientific and Political Biography

Abbasali Amid Zanjani, (born in Zanjan in April 1316 SH – died in Tehran in November 1390) was a *mujtahid* who graduated from the Qom Seminary (from 1330 SH) and the Najaf Seminary (from 1341-1346 SH) and was a student of Ayatollah Boroujerdi, Imam Khomeini, and Ayatollah Khoei, who was an expert in the two fields of political jurisprudence and law and had numerous writings. Amid Zanjani also participated in the lessons of other Najaf teachers such as Hakim and Shahroudi.

He has been active in the field of teaching Islamic law in universities, authoring jurisprudential and legal works, establishing or supervising and managing scientific and university centers, as well as membership in various scientific and cultural councils, and being a prominent figure in 1385 SH (sixth term) and a model professor in the country in 1386 SH (presidency and Ministry of Science, Research and Technology) are among his honors.[1]

Amid Zanjani has political and executive activities and is one of the companions of Imam Khomeini in Qom and Najaf, who after the victory of the Islamic Revolution held responsibilities such as representing the Islamic Consultative Assembly, membership in the Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution and the Council for the Revision of the Constitution, and the presidency of Tehran University (1384 to 1386 SH).

Scientific and Jurisprudential Works and Writings

Template:Other books Amid Zanjani is considered one of the pioneers of teaching constitutional and public law from the perspective of Islam in universities. 35 works by Amid Zanjani have been left on various jurisprudential, legal, political, theological, mystical, and Quranic sciences. Political jurisprudence is one of the most frequent topics in his teaching and writings, and the ten-volume collection of political jurisprudence is his most famous work, which, along with Supplement to Political Jurisprudence and Encyclopedia of Political Jurisprudence, completes his collection of political jurisprudence.

The foundations of constitutional law, the foundations of human rights in Islam and the contemporary world, the constitutional law of Iran, international humanitarian law from the perspective of Islam, an introduction to comparative Islamic law, comparative constitutional law, and minority rights are also the titles of his works in the field of law.

More than 12 other books by Amid Zanjani have also been published, most of which are in the field of jurisprudence; such as Rules of Jurisprudence in 4 volumes, jurisprudential foundations of the generalities of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran, causes of guarantee, verses of rulings, and several other books. His collection of works has also been published in the form of software by the Noor Computer Organization.

Political Jurisprudence

Amid Zanjani has published several works in the field of political jurisprudence; the ten-volume course of political jurisprudence is the most famous of them. An Introduction to Political Jurisprudence, 1382 SH, Political Jurisprudence, 1388 SH, Essentials of Political Jurisprudence, and two-volume Encyclopedia of Political Jurisprudence, in collaboration with Ibrahim Mousazadeh, and Supplement to Political Jurisprudence are his other works in the field of political jurisprudence. In the same vein, the Foundations of Islamic Political Thought has also been published by the Research Institute of Culture and Islamic Thought.

Full-fledged Defense of Absolute Guardianship of the Jurist and the Islamic Republic System

Based on the political teachings of Imam Khomeini, Amid Zanjani believed in the theory of absolute appointed guardianship of the jurist and has defended it throughout his jurisprudential and political works. In his view, "the line of *wilayat al-faqih* and the system of the Islamic Republic is the peak of the application of political jurisprudence and the summit of authentic Islamic movements and the point of success of all Islamic political thoughts to this day"[2] and *wilayat al-faqih* is compatible with public opinion and the free will of the people and is in line with the sovereignty of God, the Messenger, and the Infallible Imam.[3] In Amid's view, in the combination of republicanism and Islamism, the republic represents democracy and the people's right to determine their destiny, and Islam represents its content.[4] Amid Zanjani considers *wilayat al-faqih* to be the same as the *wilayat* of the Messenger of God[5] who has the right to directly interfere in affairs, but there are also several control levers to prevent his abuse.[6] Amid Zanjani's full-fledged defense of the absolute *wilayat al-faqih* and the Islamic Republic of Iran can be seen in all his works, and one of his special views, in addition to the appointed and absolute *faqih*, is the existence of divine support for the *faqih* and his distance from error. While rejecting the existence of self-centeredness, profiteering, and betrayal in the *wali-ye faqih*, he believes that although the *wali-ye faqih* is not infallible, he is under the special grace and support of God and is far from error.[7]

Political Development and Expansion of Freedoms, the Most Important Challenge of Political Jurisprudence

In examining the historical and jurisprudential "political thought in the contemporary Islamic world," in the field of Shia and Sunni jurisprudence, Amid considers the most important future challenge to be the combination of *khilafat* (in Sunni political thought) and *imamat* (in Shia political thought) with political development and the expansion of freedoms. In his view, in Sunni jurisprudence, with the closure of the door of *ijtihad*, we are faced with a crisis of democracy and the Islamic political system in Islamic countries.[8] He introduces the political thought of *wilayat al-faqih* as a flexible thought in which the element of *imamat* is fixed and comprehensive, and the concepts of justice, *ijtihad*, and political insight are its changing and flexible matters and can be combined with many principles, foundations, and methods of democracy.[9]

Solving the Challenge of Democracy, Nationalism, and Modernism in the Form of Moderate Islam

Amid Zanjani emphasizes the ideological and monotheistic element of Islamic political thought and proposes theories consistent with *imamat* or *khilafat* for the legitimacy of the political systems of Islamic countries. He reports that along with following the path of the West and the current experience of secular man, Islamic democracy, nationalism, and modernism are three ideas that Islamic thinkers in different Islamic countries have welcomed.[10] He believes that the ideology of nationalism, even Arab nationalism (the Arab nation), is in conflict with the unity of the Islamic *umma* and is aligned with racism. Although some have used a combination of Arab and Islamic nationalism, in contrast, someone like Seyyed Jamaluddin Asadabadi has presented the "Islamic society" in opposition to the "Arab society."[11]

In the discussion of "Iranian nationalism," Amid rejects the accusation that Shiism is a kind of Iranian nationalism movement against the ruling Islam and the national feeling of Iranians in compensating for the defeat against Arab Islam.[12] While emphasizing the protection of the past heritage and remaining committed to religious tradition and heritage, he does not necessarily consider it backwardness and turning away from modernism and accepts modernism in executive affairs and "what has no text in it" and in the face of progressive Islam (supporters of modernism) and Salafi Islam (opponents of modernism) calls his name "moderate Islam," which he also sees Allameh Tabatabai and Imam Khomeini in this category.[13]

The Challenge of Republicanism and Islamism and the Vulnerability of the Islamic Revolution

In Amid Zanjani's view, the challenge of political power and people's freedom is one of the vulnerable points of revolutions. In the Islamic Revolution of Iran, there is also this challenge between Islamism (*wilayat al-faqih*) and democracy and people's freedom. This challenge can create two types of deviation in terms of knowledge and application: 1) An approach that considers *wilayat al-faqih* a dictator and a factor in depriving freedoms, and 2) An approach that interprets people's freedom as rebellion and liberation towards corruption.[14]

Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Kufr in the New World

In addition to personal, public, and state ownership, Islam has also attributed lands to nations based on belief and ideology[15] and on this basis, the division of Dar al-Islam and Dar al-Kufr has been formed.[16] In jurisprudence, the jurisprudential homeland is discussed with religious effects,[17] but the ideal of Islam is to create a unified global *umma* and country and the rule of God's law on earth;[18] therefore, geographical boundaries do not have real validity[19] and until the realization of global Islamic rule, peaceful methods must be used, just as the Prophet of Islam (PBUH) formed the Islamic country and government instead of the tribal system of Hejaz and the Arabian Peninsula with peaceful methods.[20]

Political Economy of Islam and the Theory of Adjustment

Amid Zanjani sees Islamic economics within the political system of Islam and believes that the system of *imamat* governs economic management, and therefore the Imam of the *umma* can also act in economic affairs as required by expediency.[21] Also, in his view, both the free and state economic systems have a special place in the Islamic economic system, and accepting none means denying the other. He criticizes the theory of Islamic free economy based on the slogan "People are in control of their property" and also the theory of Islamic socialism based on the slogan "The wealth of God" and proposes the theory of adjustment and warns about the tendency towards free markets and privatization.[22]

In the methodology of the political economy of Islam, he mentions the questions and challenges ahead; such as: the use of induction and experience consistent with custom in the rulings of "what has no text in it", the use of analogy in economic issues in Sunni jurisprudence, the impact of the inflation issue on the norms of the Islamic economy (such as alimony, fair wage, and the ruling of *riba*), the impact of the requirements of time and place in evaluating religious texts and jurisprudential inference, the degree of acceptability, rationality, and benefits and harms of rulings and its difference and extent in Islamic and Western economic models, the role and limits of the intervention of *imamat* in the political economy system of Islam.[23]

The Place of Justice in Various Dimensions of Islamic Thought

Justice is one of the topics of special attention to Amid Zanjani. In explaining the ideological roots of the Islamic Revolution of Iran, he introduces the establishment and expansion of justice as one of the foundations of political thought in the Quran and believes that according to the Quranic view, justice, in addition to being one of the prominent divine attributes in creation and the best human characteristic, is also one of the two basic goals of the prophets' mission.[24] He has also considered justice as a condition for *khilafat* and *imamat* in political jurisprudence[25] In the discussion of the role of reason in discovering expediency in the variable rulings of Islam, he also introduces justice as the main criterion for determining the right and religious ruling.[26]

In the issue of human rights, justice is also the measure of legal rules, one example of which is the rights of minorities.[27] The implementation and generalization of justice, in addition to public and internal security[28] also plays a role in international society and global security, and the world is forced to reach and achieve the correct concept of justice in order to achieve security[29] In Islamic economics and political economy, the ultimate goal is nothing but justice.[30] Also, in the right to justice, education, social security, and public supervision, justice should not be forgotten[31]

Supervision of the Actions of the Islamic Government

Amid Zanjani considers supervision of the actions of the government and administrative justice to be one of the key components of religious government[32] and states that it includes supervision of all aspects of the government's performance, including the administrative system[33] He has considered the legitimacy of supervision and justice in the administrative system to be dependent on the legitimacy of the political system and in the Islamic Republic of Iran, he has considered the principles of republicanism and Islamism to be the two main pillars of the system's legitimacy, and these principles form the basis of administrative supervisions and laws.[34] In his view, enjoining good and forbidding evil is both a common duty between the government and the people and an important legal and religious tool.[35]

Human Rights

Amid Zanjani has authored several books on the subject of human rights, either independently or within collections: 1- International Law of Islam (volume three of the political jurisprudence collection), 2- Rights and Rules of Conflicts in the Field of Islamic Jihad and International Law of Islam (volume five of the political jurisprudence collection), 3- Principles and Regulations Governing Armed Conflicts (volume six of the political jurisprudence collection), 4- International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, 5- Minority Rights in Islamic Jurisprudence, 6- Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, 7- International Humanitarian Law from the Perspective of Islam, which he authored in his seventh decade of life at the suggestion of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Tehran.[36]

Fundamental Difference in Anthropology in Global and Islamic Human Rights

In his human rights works, Amid Zanjani has had a comparative study between global and Islamic human rights.[37] In his view, the emphasis on human rights in the West, its inclusion in the constitutions of some countries, and its inclusion as indicators of democracy and modernity are rooted in Western culture and their scientific advances.[38]

From Amid Zanjani's point of view, the main issues of human rights, such as dignity, equality, security, justice, and legitimate freedoms, exist in the view of Islam and have even been given more attention than Western thought.[39] Also, the attention and focus of Western freedom and human rights are on capitalism, satisfying the desires and material demands of the majority, but in Islam, freedom and human rights are based on monotheism and belief in God and absolute obedience to Him.[40]

Dignity and Equality of Human Beings, the Main Issue of Human Rights

Amid Zanjani has considered human dignity and equality to be the main issues of human rights and the most important of them. This dignity and equality are not only in the social dimension; but also in the individual dimension, human dignity must be preserved. He gives the example of the cells of the body and explains that human beings should not be tools to serve society and the government, just like the cells that are completely at the disposal of the body, but each human being must have his own independence, will, and distinct personality. For this reason, the unity of the truth of human beings is not due to racial, historical, cultural, and linguistic similarities and issues like these, but the existence of common values and human dignity causes the true unity among human beings.

In Islam, even more attention has been paid to the dignity and equality of human beings than in other religions and schools, and this principle is the first basis of the social system of Islam, and the only difference that has been accepted in Islam between human beings is the creative difference between men and women, while their human identity is equal. Some of the legal differences between these two genders also stem from this creative difference, not from inequality or lack of dignity.[41]

The Principle of Global Solidarity and International Cooperation of Mankind

One of the principles that Amid Zanjani raises from the perspective of Islam is the principle of global-human solidarity. According to this principle, Islam's view of mankind is based on brotherhood, and blood, racial, and ethnic separations have no importance or authenticity in the path of humanity and obedience to God and do not create any discrimination or privilege for anyone.[42] The principle of equality, like the principle of freedom, is absolute[43] and according to the verses of the Quran, mankind was created from a couple, and all human beings are children of one father and mother, and there is no privilege for any individual or family.[44]

The principle of equality is also one of the components of the principle of invitation to achieve a single global *umma*; because God has considered Islam to be the last religion of the world and all of humanity to be one *umma*.[45] In the light of this principle, international cooperation will take shape in solving global economic and political problems, as well as fighting physical and mental illnesses.[46]

The Right to Freedom of Residence

In Islam, the freedom to choose and change homeland, residence, and domicile is legitimate for all human beings, both Muslim and non-Muslim.[47] In Islam, the right to freedom of housing is also reserved for minorities and non-Muslims within the framework of the *dhimma* or *aman* contract; except in prohibited and forbidden areas such as the city of Mecca.[48] The residence of Muslims in the lands of *kufr* and non-Islamic countries is without objection if they are able to perform religious duties and establish Islamic rituals, and otherwise, their migration to Islamic lands is obligatory; except in special and exceptional cases.[49]

Rights of Religious Minorities and Payment of Jizya

In his works, Amid Zanjani has examined the rights of minorities, especially the nature of the *dhimma* contract, and has introduced it as a "national unity pact." He believes that this contract is a factor for national unity and solidarity, as well as cooperation between the Islamic community and non-Muslim groups in the realm of Islamic government.[50] From his point of view, the financial commitment arising from the *dhimma* contract (*jizya*), contrary to popular belief, is neither as a punishment for not accepting Islam nor to humiliate minorities. This contract is based on three key principles: (1) the consent and agreement of both parties to the contract, (2) the insignificance of the amount of *jizya* and attention to the minimum facilities of minorities, (3) the exemption of non-Muslim allies from the financial, defensive, and military responsibilities that are the responsibility of the Muslim community.[51]

In addition, the *dhimma* contract creates heavy and specific obligations for the Islamic community, which ensures their comprehensive immunity,[52] religious freedom,[53] and judicial independence[54] and gives religious minorities freedom of housing and the right to choose a place of residence, with the exception of prohibited areas,[55] and economic freedom within the framework of Islamic economic principles, such as the prohibition of *riba*[56] and gives them civil rights.[57] On this basis, minorities will have ethical and social interactions with Muslims[58] and enjoy the freedom of social activities based on Islamic and Quranic logic.[59]

Applying the Renunciation of Political Citizenship to Apostasy

In Amid Zanjani's legal view, apostasy is a kind of renunciation of Islamic citizenship and nationality, and for this reason, he has brought the religious discussion of apostasy under the subject of citizenship and nationality. In his view, in the Islamic legal system, faith is based on freedom of thought and belief and with full awareness; therefore, there is no permission to violate and breach the contract unilaterally, and therefore, in Islamic law, apostasy is considered one of the major crimes.[60] that its proof is possible based on the ruling of Islamic courts, confession and admission of apostasy, or the testimony of valid witnesses.[61]

Examples of apostasy today are the renunciation of citizenship of a Muslim woman through marriage to a non-Muslim man in some countries[62] and the renunciation of citizenship when a part of the Islamic lands separates from the Islamic government.[63] The external manifestation and practical realization of apostasy has three states:

- Practical apostasy with the intentional commission of a forbidden act with the aim of enmity or ridicule.

- Practical apostasy by refusing and refraining from performing an obligatory act and implementing Islamic laws with the aim of denial or justification.

- Verbal apostasy by criticizing and verbally denying some of the laws of Islam and introducing Islam as an incomplete and inadequate religion and considering Islam as a factor of the decline of Muslims[64]

The Sacred Shrine of Mecca, an Islamic International Zone

The Abrahamic Hajj is one of the topics that Amid Zanjani has spoken and written about. In the book "On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj," he considers the sacred shrine of the city of Mecca to belong to all Muslims according to the verses of the Quran[65] and introduces it as an Islamic international zone. He believes that worship in the shrine and the Holy Mosque is not limited to the principles of one religion and point of view.[66] Also, according to the belief of many Islamic scholars, the shrine of Mecca is a free Islamic land and cannot be owned.[67]

In this book, Amid Zanjani also deals with the political philosophy of disavowal of polytheists and the views of Shia and Sunni and considers the view of Sunnis who believe that disavowal has no independent title and that the verse of disavowal was only an announcement of the cancellation of contracts violated with polytheists to be in clear opposition to the Quran.[68]

Footnotes

- ↑ Haj-Beigi Kendari, Memoirs of Hojjat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen Abbasali Amid Zanjani; General Department of Cultural Affairs and Public Relations of the Islamic Consultative Assembly, Introduction of Representatives of the Islamic Consultative Assembly.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 1, p. 23.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 1, pp. 68 to 79.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 1, pp. 193 to 196.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 1, p. 259.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 1, p. 217.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 2, p. 276, vol. 6, p. 123; Political Jurisprudence, vol. 7, p. 486; Encyclopedia of Political Jurisprudence, vol. 2, pp. 118 and 702.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 179 to 189.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 11 to 178.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 40 to 60.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 61 to 83.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 84 to 122.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, pp. 204 to 218.

- ↑ Islamic Revolution, Causes, Issues, and Political System, p. 266.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, pp. 30 and 119.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 30. 108.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 34.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 38.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 38.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 64.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 4, pp. 13 and 14.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 4, pp. 190 to 200.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 4, pp. 201 to 231.

- ↑ Islamic Revolution of Iran; Causes, Issues, and Political System, p. 61.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 7, p. 163.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 9, p. 416.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 10, p. 414

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, p. 184

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 3, p. 422; International Humanitarian Law from the Perspective of Islam, pp. 75 and 82.

- ↑ Political Jurisprudence, vol. 4, p. 218.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 208-210; Political Jurisprudence, vol. 7, p. 555.

- ↑ Supervision of the Actions of the Government, p. 1.

- ↑ Supervision of the Actions of the Government, p. 8.

- ↑ Supervision of the Actions of the Government, p. 273.

- ↑ Supervision of the Actions of the Government, pp. 74 and 78.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 1: Introduction.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 86-149.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 211-230.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 173-232.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 187-191.

- ↑ Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, pp. 176-182; International Humanitarian Law from the Perspective of Islam, pp. 25-32.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 71.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 73.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 74.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 83.

- ↑ International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, p. 85.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, p. 20.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, pp. 164-167.

- ↑ Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects, pp. 155-157.

- ↑ Minority Rights, p. 57.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 96-98.

- ↑ Minority Rights, p. 136.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 142, 157, 164, 166, 168.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 178-184.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 170-172.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 191-203.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 204-220.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 221-250.

- ↑ Minority Rights, pp. 251-259.

- ↑ Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, p. 117.

- ↑ Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, p. 125.

- ↑ Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, p. 113.

- ↑ Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, p. 114.

- ↑ Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, pp. 118 and 119.

- ↑ On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj, p. 187.

- ↑ On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj, p. 189.

- ↑ On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj, p. 190.

- ↑ On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj, p. 118.

Resources

- Haj-Beigi Kendari, Mohammad Ali, Memoirs of Hojjat al-Islam wal-Muslimeen Abbasali Amid Zanjani, Tehran, Center for Islamic Revolution Documents, 1379 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Islamic Revolution: Causes, Issues, and Political System, Tehran, Daftar Nashr Maaref, 1391 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Foundations of Nationality in the Ideal Islamic Society, Tehran, Bonyad Besat, 1361 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasai, Research and Investigation in the History of Sufism, Tehran, Dar al-Kitab al-Islamiyah, 1367 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Minority Rights, Tehran, Daftar Nashr Farhang Islami, 1362 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali and Hossein Norouzi, International Humanitarian Law from the Perspective of Islam, Tehran, Tehran University, 1390 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, International Treaty Law and Diplomacy in Islam, Tehran, Samt, 1379 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, in collaboration with others, Encyclopedia of Political Jurisprudence, Tehran, Tehran University, 1389 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, On the Way to Establishing the Abrahamic Hajj, Tehran, Nashr Mashar, 1375 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Political Jurisprudence, ten volumes, Tehran, Amirkabir, various years.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Foundations of Human Rights in Islam and the Contemporary World, Tehran, Majd, 1388 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali and Ibrahim Mousazadeh, Supervision of the Actions of the Government and Administrative Justice, Tehran, Tehran University, 1389 SH.

- Amid Zanjani, Abbasali, Homeland and Land and Its Legal Effects from the Perspective of Islamic Jurisprudence, Tehran, Daftar Nashr Farhang Islami, 1364 SH.

- Introduction of Representatives of the Islamic Consultative Assembly from the Beginning of the Glorious Islamic Revolution to the End of the Fifth Legislative Period (1378), Tehran, General Department of Cultural Affairs and Public Relations of the Islamic Consultative Assembly.