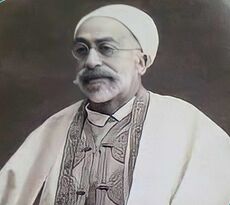

Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur

Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur(in persian: محمدطاهر بن عاشور) (1296-1393 AH) was a Tunisian exegete, jurist, and theorist of Maqasid al-Shari'a (the higher objectives of Islamic law), renowned in the Islamic world for his book "Maqasid al-Shari'a" and his commentary "Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir." Ibn Ashur, an Ash'ari in creed and Maliki in jurisprudence, is considered a reformist scholar who initiated many intellectual and social transformations and innovations in Tunisia.

| |

| Name | Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur |

|---|---|

| Age | 1879 CE / 1296 AH - 1973 CE / 1393 AH |

| Nationality | Tunisian |

- Abstract

Ibn Ashur viewed Islam as a religion of tolerance and leniency, and for this reason, he believed it possessed the capacity for presence in the social and political spheres, approaching the divine texts from this perspective. He criticized secular Muslims who held a minimalist view of Islam and did not believe Islam was separate from the realm of governance.

Relying on his reformist approach, Ibn Ashur saw jurisprudence (fiqh) as efficient and contemporary. He pursued this concern by focusing on the objectives of the Lawgiver (Maqasid al-Shari'a), believing in the capacity for tolerance and leniency, and the rationalizability of social rulings. Based on this, he re-examined and expressed new opinions on numerous rulings, such as the sacrifice in Hajj, the striking of women, the structure of government, and hardship in fasting.

Ibn Ashur proposed the Maqasid al-Shari'a to modernize the principles of jurisprudence (Usul al-Fiqh), and perhaps even as a potential replacement for it. Through his theory of Maqasid, he sought to transition from a fragmented (detail-oriented) understanding of rulings and an individualistic view to a social and holistic perspective. Nevertheless, Ibn Ashur's innovations in Maqasid-oriented thought, his exegesis, and his social perspective on religious teachings have not escaped the notice of critics, and some scholars have attempted to analyze the positive and negative consequences of his intellectual works.

Biography of Ibn Ashur

Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur (1879-1973 CE), the Shaykh al-Islam of the Maliki school in Tunisia and also the Shaykh of the Zaytuna Mosque, was born in "La Marsa" in the northern suburbs of Tunis. He memorized the Quran and also became familiar with the French language. He is considered a literary scholar, exegete, jurist (usuli), and theorist in the fields of Maqasid al-Shari'a and the socio-political system of religion.[1] He held licenses for ijtihad (independent legal reasoning) from four of his teachers. Influenced by the intellectual revolution of figures like Jamal al-Din al-Afghani and Muhammad Abduh, he became a leading figure of transformation in his surrounding society. He passed away on Saturday, Rajab 13, 1394 AH.

Works of Ibn Ashur

Ibn Ashur has numerous publications. Although these works do not fit into a single specific field, their common feature is their novelty. He has nearly 38 published works and many unpublished ones.[2] Some of his works that reflect his thoughts on the contemporary problems of Muslims include:

- Tafsir al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir: This scientific and Quranic encyclopedia is one of his most enduring works and a major commentary of the modern era, structured in the style of Quranic exegesis by the Quran.[3] Additionally, as a methodological pillar, it is based on attention to hadiths, poetry, linguistics, grammar, rhetoric, and more, which some have termed "diraya" (knowledge-based interpretation).[4] *Al-Tahrir* was compiled with a reformist tone and approach; therefore, it was not oblivious to the questions and challenges of its time.

- Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya: In this book, while explaining the position of the knowledge of Maqasid al-Shari'a in jurisprudence, he suggests replacing the science of Usul al-Fiqh with this knowledge.

- Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam (Principles of the Social System in Islam): In this work, Ibn Ashur examines the factors of progress and stagnation in early Islamic society. While emphasizing the alignment of the foundations of the social system with human nature, he identifies moderation, high-mindedness, justice-orientation, and conventionality as its characteristics.

- Naqd 'Ilmi li-Kitab al-Islam wa Usul al-Hukm (A Scientific Critique of the Book 'Islam and the Principles of Governance'): In this book, Ibn Ashur, emphasizing the inseparability of religion and politics, critiques the thought based on this separation, which was proposed by figures like Ali Abdel Raziq.

Ibn Ashur and Creating Capacity for Fiqh's Presence in the Modern World

Maliki jurisprudence has characteristics that have allowed innovation to occur with greater ease compared to other schools. These features include: (a) flexibility in principles, (b) attention to the Maqasid al-Shari'a, (c) jurisprudential consideration of public interest in the domain of social rulings, and (d) attention to matters like "khilaf" (scholarly disagreement) and the "place of 'urf' (custom)" and the like, which contribute to the intellectual strength and broad perspective of the jurists of this school.[5]

Part of Ibn Ashur's innovations in the jurisprudential field arose from his jurisprudential inclination, and another part stemmed from his perspective on Sharia and religion.

Open-mindedness and Lack of Dogmatism

One of the topics that Ibn Ashur focused on in the verses of rulings (Ayat al-Ahkam) is open-mindedness and the absence of jurisprudential dogmatism,[6] which originates from his attachment to Maliki jurisprudence. This feature is both a characteristic of the exegetical school of the Islamic West[7] and has been considered a feature of the Maliki school.[8]

Expansion in the Use of Masalih Mursala (Unrestricted Public Interests)

Imam Malik acted upon *masalih mursala* more than other imams and advocated for an expanded use of it.[9] Ibn Ashur also extensively discusses the concept of public interest (*maslaha*) in Sharia in his "Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya." By dividing interest into general and specific, he states that general interest is anything that benefits the public, while specific interest is that which secures the well-being of each individual without considering their social status.[10]

The Theory of Leniency and Tolerance in Sharia

Another of Ibn Ashur's foundational principles in approaching the verses of rulings is his belief in the theory of tolerance and leniency. Both in his commentary and his other works, he has mentioned tolerance as one of the most important fundamental and theoretical pillars of Islam and a key foundation of Sharia.

The Nature and Place of Tolerance in Islam in Ibn Ashur's Thought

Ibn Ashur considers tolerance and forbearance with believers to be the primary characteristic of Islamic Sharia and its greatest objective.[11] He cites verses such as Quran 2:85, Quran 22:78, and Quran 5:6, along with several narrations from the Prophet (s), as evidence for the correctness of the theory of tolerance in Islam.[12] He considers tolerance to be a necessary consequence of Islam's nature-based (*fitri*) foundation and asserts that the most significant difference between Islam and other religions is its basis in human nature.[13] According to Ibn Ashur, tolerance is a boundary between strictness and laxity and reverts to the concept of moderation and being a middle way.[14]

In Ibn Ashur's view, tolerance has a profound effect on the spread of the Sharia and the continuation of its vitality. By bringing together all this evidence, he concludes that tolerance is one of the most important religious topics.[15] He considers the divine Sharia to be one that possesses tolerance, avoidance of harshness, stability and change in legislation, and equality and freedom.[16]

Applying Tolerance to the Rulings of Fasting

Based on the principle of tolerance in Sharia, Ibn Ashur, citing the word "yutiqunahu" (who can do it [with hardship]) in Quran 2:184, argues for the permissibility of breaking the fast for all those for whom fasting is arduous or who anticipate potential harm, such as the elderly, and breastfeeding or pregnant women. This ruling will vary depending on different temperaments and the times of fasting, and with consideration for the fasting person's occupation. Therefore, those with difficult professions have the same ruling as the elderly and breastfeeding or pregnant women.[17]

The Rationalizability of Rulings: A Foundation for Engagement with Modern Rationality

One of the foundations of interest-based reasoning (*maslahat-gara'i*) and the rationalization of fiqh is the extent of adherence to their literal meanings versus opening the field to rationalization (*ta'lil*). Ibn Ashur is among the scholars who accepted the rationalizability of rulings.[18]

He based his theory of Maqasid al-Shari'a on three rational foundations: human nature (*fitra*), public interest (*maslaha*), and rationalization (*ta'lil*). Ibn Ashur linked the rationalization of religious thought within the sphere of legislation to the belief in the rationalizability of rulings, referring to it as "the rationality of legislation."[19] He believed that: denying rationalization would lead to rigidity based on the literal meanings of religious texts in argumentation, which in turn would lead the Sharia into a state of stagnation and halt in establishing religious rulings for new events, and there is a fear that it would lead to negating the capabilities of the Sharia for all times and places.[20]

Apart from purely ritualistic rulings, Ibn Ashur considers all devotional and transactional rulings to be rationalizable, and their underlying causes can be discovered through ijtihad.[21] This theory led to criticism from several thinkers against Ibn Ashur, questioning why he sought causes for even the most minor jurisprudential issues.[22]

Regarding the Striking of Women

In the discussion of striking women under Quran 4:34, Ibn Ashur emphasizes that one cannot argue for the permissibility of hitting a wife based on a "strike" (*darb*) that originates from disobedience and displeasure approved by Arab custom (*'urf*); because this law was based on the custom of Arab society at that time, and the differences among people were also considered. In his commentary, to prevent men from abusing this ruling, Ibn Ashur, emphasizing that "few are those who punish in proportion to the sin," points to the role of the government in this matter, saying: to prevent men's abuse of such rulings, the government can take on the implementation of these rulings itself and punish anyone who arbitrarily takes them into their own hands.[23]

Ibn Ashur and Maqasid al-Shari'a

Years after the first publication of the book "Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya" by Ibn Ashur, this book and its author's views remain an important source on the objectives of Sharia and are subject to critique and analysis by scholars. Among these are the books "Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur" and "Al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur wa Kitabuhu Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya." Ibn Ashur, whom Ahmad al-Raysuni referred to as the "Second Teacher" in Maqasid,[24] raised the concern for Maqasid al-Shari'a with his book "Alaysa al-Subhu bi-Qarib."[25]

The theory of Maqasid, as Ismail al-Hasani writes, in Ibn Ashur's view: is manifested in the thought of achieving individual, social, and civilizational well-being, and its path is the reform of the world through the reformation of man, who has dominion over the world. This objective governs all other objectives.[26] Some have considered Ibn Ashur's theory of Maqasid to be the end of the science of Usul al-Fiqh, as they believe: the theory of Maqasid is a transition from a fragmented (detail-oriented) understanding of rulings and viewing them individually to a social and general perspective.[27]

Classification of Maqasid

According to Ahmad al-Raysuni, one of Ibn Ashur's innovations is that he opened a new dimension for the perspective of Maqasid, which lies between the general and specific objectives.[28] In another of his works, al-Raysuni writes: The objectives of Sharia are of three types; general objectives, specific objectives, and particular objectives.[29] Al-Raysuni defines particular objectives as: objectives that are above the specific objectives and below the general ones, and they pertain to a specific legislation.[30] Ibn Ashur believes that obtaining the objectives is possible through three ways: induction (*istiqra'*), clear Quranic evidence, and consecutively transmitted Sunnah (*mutawatir*).[31]

Ismail al-Hasani, who has tried to take a critical look at Ibn Ashur's theory, believes that the ways Ibn Ashur relied on—in proving the Maqasid al-Shari'a—only lead to general objectives; because they either revert to induction, ... or to Quranic evidence that indicates a general objective.[32] He believes: the ways of proving the objectives according to Ibn Ashur are not confined to what he presented in a small part of his book on Maqasid, but rather, contemplation of the methodology of the discussion leads the researcher to discover other ways of proving the objectives.[33]

Maqasid-Orientation and the Hajj Sacrifice

Ibn Ashur is among the jurists who, by adhering to the knowledge of Maqasid and utilizing divine verses, years ago issued a fatwa for the optimal use of the sacrifice in Hajj. Under Quran 22:37, "Their meat will not reach Allah, nor will their blood," while emphasizing the necessity of observing the Lawgiver's objectives in legislating this ruling—which is to alleviate the needs of the poor through this means while also preserving wealth—he points to the Lawgiver's disapproval of neglecting this ruling and says: In my opinion, both situations of selling the sacrificial meat or freezing the surplus beyond people's needs during the days of Hajj so that the needy can benefit from it throughout the year, are more in line with the objectives of the Sharia; because it prevents the waste of surplus meat and preserves people's wealth.[34]

Ibn Ashur and the Foundations of the Social System of Religion

Ibn Ashur considers the social and political spheres to be among the concerns of religion and, unlike figures such as Ali Abdel Raziq, does not recognize secularism. He places the foundations of the social system of religion under two arts: the first art is based on noble ethics, justice, fairness, unity, and philanthropy, and the second art is based on equality, freedom, rights, justice, and tolerance, etc.[35]

In his book "Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam," given his social perspective on Islam and religious governance, Ibn Ashur speaks in detail about rulers and their conditions and methods of selection. He also considers this perspective in his commentary. For example, in his commentary on Quran 4:59, he considers "those in authority" (*uli al-amr*) to be those to whom the people have entrusted their governance.[36] From this statement by Ibn Ashur, it can be understood that he considers the method of selection to be something in line with modern democracies; however, when it comes to explaining the conditions of rulers, he can no longer be seen as aligned with modern ideas regarding governance; because in his belief, "those in authority" in the view of the Sharia are a specific group of religious leaders of the Muslim community whose attributes must be found in the Sharia.[37]

Religious Government and Human Freedoms

Another dimension of Ibn Ashur's political thought is his attention to the scope of religious governments and their limitation to respecting human freedoms. He believes that the main duties of a religious government are to ensure equality, liberty, protection of human rights, justice, financial order, and defense of the country, etc. In the book Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam, Ibn Ashur divides freedom into freedom of belief, freedom of thought, freedom of expression, and freedom of action.[38] In judging between the types of freedoms and valuing them, he assesses freedom of belief as the most extensive type of freedom; because its scope is wide and its only criterion is rational evidence and proofs.[39]

Freedom of Thought and Action

Ibn Ashur believes that since reason and thought are the main essence of man, freedom of thought and expression are among the undeniable rights of all human beings, and transgressing this right is a great injustice to people. By further explaining the concept and aspects of each of these freedoms, Ibn Ashur clarifies their relationship and proportion to a religious society. Regarding freedom in the realm of behavior, he says: limiting this type of freedom for the non-infallible is very difficult; therefore, it is obligatory for rulers to be cautious and not resort to limiting freedoms beyond what leads to repelling corruption and attracting public interest; because that would be oppression.

Ibn Ashur goes so far in his belief in human freedoms that he believes the verse "There is no compulsion in religion" abrogates the verses of fighting (*qital*); because Islam is a religion that must be chosen with freedom and choice. The importance of this point lies in the fact that in the political theory of many of Ibn Ashur's co-religionists, obedience is the principle, and opposition to the ruler is considered rebellion against the Caliph of Islam.

Governmental Position of the Prophet of Islam (s)

The belief in the existence of human freedoms is well manifested in Ibn Ashur's intellectual system, to the extent that he believes the Prophet (s) is also a human being like us, and what he has is not from him; rather, it is revealed to him. In his belief, the Prophet was not chosen as a scholar to be responsible for answering people's questions; rather, he has knowledge on par with others, and God, in the domains of monotheism and legislation, reveals to him whatever He deems beneficial to convey to the people. He explicitly states that the command to obey God and the Messenger is a command to obey the Sharia, and the Prophet's commands are to be obeyed in the circle of religious matters, and in social matters, disobedience does not entail sin.[40]

Selection of the Ruler by the People

Ibn Ashur considers Islamic government to be a democratic government based on religious rules derived from Quranic principles, prophetic tradition, and the opinions of jurists. In his belief, religious governance is not hereditary or personal, and the only way to choose a ruler is through the votes of the public. In applying this theory, he refers to the quality of the selection of the Islamic ruler and ultimately leaves it to the people, saying: Since God has called us to obey "those in authority," we understand that in the view of the Sharia, these are specific individuals. They are the leaders of the community and its trustees. The establishment of this attribute for them must also be based on the Sharia. The way to prove the attribute of "those in authority" through the Sharia is either by the Caliph or the community of Muslims (ahl al-hall wa al-'aqd).[41]

Considering the Ruling on Slavery in Islam as Temporary

Ibn Ashur's analysis of slavery, given his intellectual foundations, tends towards the negation of slavery by eliminating its causes. In his belief, what happened in early Islam regarding slavery was a temporary strategy appropriate for the Arabs of the era of revelation, and nothing more. According to him, Islam directed its efforts towards eradicating all factors of slavery, and only the factor of captivity in war remained, and that was due to the positive effects it had for the Islamic community, which he also evaluates as a kind of deterrent tactic and believes that Islam has compensated for even this amount through the various ways it has opened for the freedom of slaves.

Critique and Review of Works and Views

Due to his status in the fields of exegesis, jurisprudence, legal principles, Maqasid-orientation, and his critique of secularist views on the relationship between religion and politics, Ibn Ashur has attracted the attention of scholars, and his works and views have faced critical examination. *Naqd al-Fikr al-Maqasidi 'ind al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur* by Muhammad al-Madnini, a collection of articles titled *Maqasid al-Shari'a 'ind al-Tahir ibn Ashur*, the book *Fiqh al-Insan* by Amr al-Sha'ir, *Manhaj al-Imam al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi Tafsir "Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir"* by Nabil Ahmad Saqr, and *Madkhal ila al-'Aql al-Usuli lil-Imam al-Tahir ibn Ashur* by Abd al-Fattah ibn al-Yamani al-Zuwayni are examples of works and scholars who have studied Ibn Ashur's legacy with a critical eye.

Inattention to the Historicity of the Maqasid of Sharia

Ibn Ashur's Maqasid-based perspective is founded on objectives formed within the historical tradition of Muslims, just as other Maqasid-oriented scholars have done. In this view, the historicity of the objectives formed in Muslim thought is effectively ignored. And the question remains: is it not possible to re-read and renew the objectives over time?

For example, in the discussion of polygyny, Ibn Ashur, with his Maqasid-oriented view, refers to the principle of the Sharia's expansiveness and avoidance of hardship for people. He writes: Since Islam forbade adultery and was very strict in prohibiting what leads to corruption in morals, lineage, and the family system, on the other hand, it has opened a new scope for those who need polygyny.[42] But it is clear that Ibn Ashur completely ignores women as the other side of this ruling and obligation. Whereas one might come to believe that the objectives should be seen as non-gendered and, indeed, public. In other words, if this verse has objectives, both the nature of men and the nature of women must be considered in it; therefore, addressing only one side of this discussion can lead to challenges.

Footnotes

- ↑ Al-Misawi, *Al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur wa Kitabuhu Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 80.

- ↑ Al-Ghali, *Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur: Hayatuhu wa Atharuh*; Al-Hasani, *Maqasid Shari'at az Negah-e Ibn Ashur*, pp. 142-150.

- ↑ Saqr, *Manhaj al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi al-Tafsir*, p. 54.

- ↑ Saqr, *Manhaj al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi al-Tafsir*, p. 139.

- ↑ See: Al-Zulami, *Asbab Ikhtilaf al-Fuqaha fi al-Ahkam al-Shar'iyya*, p. 51; Faraj Husayn and Al-Surayti, *Al-Nazariyyat al-'Amma fi al-Fiqh al-Islami*, p. 401; Al-Raysuni, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam al-Shatibi*, p. 299.

- ↑ Anburi, *Madkhal li-Dirasat Manhaj al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi Tafsir al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*.

- ↑ Shafiei, "Methodology of Exegesis in the Islamic Maghreb."

- ↑ Faraj Husayn and Muhammad al-Surayti, *Al-Nazariyyat al-'Amma fi al-Fiqh al-Islami wa Tarikhih*; Anburi, *Madkhal li-Dirasat Manhaj al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi Tafsir al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*.

- ↑ Faraj Husayn and Muhammad al-Surayti, *Al-Nazariyyat al-'Amma fi al-Fiqh al-Islami wa Tarikhih*, p. 400.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 279.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 268.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 21, pp. 270-271.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 21, p. 92.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 21, p. 92.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 227.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 22, p. 71; *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 223; *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, pp. 111-112.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 2, p. 167.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, pp. 93-96.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, pp. 53-58.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 47.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, pp. 240-241.

- ↑ Al-Fasi, *Maqasid al-Shari'a wa Makarimuha*, p. 1.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 4, p. 119.

- ↑ Al-Misawi, *Al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur wa Kitabuhu Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 70.

- ↑ Al-Raysuni, *Muhadarat fi Maqasid al-Shari'a*, p. 96.

- ↑ Al-Hasani, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur*, p. 231.

- ↑ Al-Misawi, *Al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur wa Kitabuhu Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, p. 46.

- ↑ Al-Raysuni, *Al-Dhari'a ila Maqasid al-Shari'a*, p. 69.

- ↑ Al-Raysuni, *Al-Fikr al-Maqasidi, Qawa'iduhu wa Fawa'iduh*, p. 15.

- ↑ Al-Raysuni, *Muhadarat fi Maqasid al-Tashri'*, p. 97.

- ↑ Al-Hasani, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur*, p. 231.

- ↑ Al-Hasani, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur*, p. 430.

- ↑ Al-Hasani, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur*, p. 430.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 16-17, p. 268.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 122.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 4, p. 165.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 4, p. 166.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 170.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 171.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, p. 174.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 4, p. 166.

- ↑ Ibn Ashur, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, vol. 4, p. 226.

References

- Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Usul al-Nizam al-Ijtima'i fi al-Islam*, 2nd ed., Algiers: Al-Mu'assasa al-Wataniyya lil-Kitab, n.d.

- Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir*, Beirut: Mu'assasat al-Tarikh, 1420 AH.

- Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, Introduction by Muhammad al-Tahir al-Misawi, Jordan: Dar al-Nafa'is, 1421 AH.

- Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Naqd 'Ilmi li-Kitab al-Islam wa Usul al-Hukm*, Cairo: Al-Matba'a al-Salafiyya, 1344 AH.

- Ibn Ashur, Muhammad al-Fadil, *Al-Haraka al-Adabiyya wa al-Fikriyya fi Tunis*, Arab League, 1955 CE.

- Al-Hasani, Isma'il, *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad Tahir ibn Ashur*, Herndon, VA: The International Institute of Islamic Thought, 1416 AH.

- Al-Raysuni, Ahmad, *Muhadarat fi Maqasid al-Shari'a*, Cairo: Dar al-Kalima, 2014 CE.

- Al-Raysuni, Ahmad, *Al-Dhari'a ila Maqasid al-Shari'a*, Cairo: Dar al-Kalima, 2016 CE.

- Al-Zulami, Mustafa Ibrahim, *Asbab Ikhtilaf al-Fuqaha fi al-Ahkam al-Shar'iyya*, Kurdistan, Iraq: Nashr Ihsan, 1435 AH.

- Al-Zahrani, Khalid ibn Ahmad, *Mawqif al-Tahir ibn Ashur min al-Imamiyya al-Ithna 'Ashariyya*, Markaz al-Maghrib al-'Arabi lil-Dirasat wa al-Tadrib, 1431 AH.

- Shafiei, Ali, "Rush-shinasi-yi Tafsir dar Maghrib-i Islami" [Methodology of Exegesis in the Islamic Maghreb], *Pazhuhesh va Hawzeh*, Qom, no. 33, 1387 Sh.

- Saqr, Nabil Ahmad, *Manhaj al-Imam al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi al-Tafsir "Al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir"*, Al-Dar al-Misriyya, 1422 AH.

- Abbas, Fadl Hasan, *Dirasat Islamiyya wa 'Arabiyya*, "Al-Tarjih al-Fiqhi fi al-Tafsir al-Shaykh al-Imam Ibn Ashur", Jordan: Dar Siraj lil-Di'aya wa al-I'lan, 1423 AH.

- Anburi, Hamid, "Madkhal li-Dirasat Manhaj al-Tahir ibn Ashur fi Tafsir al-Tahrir wa'l-Tanwir", *Dar al-Hadith al-Hasaniyya*, no. 13, 1417 AH.

- Al-Ghali, Bilqasim, *Shaykh al-Jami' al-A'zam Muhammad al-Tahir Ibn Ashur: Hayatuhu wa Atharuh*, Beirut: Dar Ibn Hazm, 1417 AH.

- Al-Fasi, Allal, *Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya wa Makarimuha*, Mu'assasat Allal al-Fasi, Dar al-Maghrib, 1993 CE.

- Faraj Husayn, Ahmad, and Abd al-Wadud Muhammad al-Surayti, *Al-Nazariyyat al-'Amma fi al-Fiqh al-Islami wa Tarikhih*, Beirut: Dar al-Nahda al-'Arabiyya, 1992 CE.

- Mehrizi, Mehdi, *Maqasid-i Shari'at az Nigah-i Ibn Ashur* (Translation of *Nazariyyat al-Maqasid 'ind al-Imam Muhammad Tahir ibn Ashur* by Isma'il al-Hasani), Tehran: Sahifeh-ye Kherad, 1383 Sh.

- Al-Misawi, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Al-Shaykh Muhammad al-Tahir ibn Ashur wa Kitabuhu Maqasid al-Shari'a al-Islamiyya*, Amman: Dar al-Nafa'is, 1999 CE.

- Al-Misawi, Muhammad al-Tahir, *Jamharat Maqalat wa Rasa'il Ibn Ashur*, Jordan: Dar al-Nafa'is, 1436 AH.